Ever wonder if human civilization could start fresh somewhere else, but without all our past mistakes? Bong Joon Ho’s sci-fi comedy “Mickey 17” asks this very question through its expendable protagonist who dies repeatedly for the sake of colonizing an ice planet.

The film cleverly uses dark humor and Robert Pattinson’s multiple iterations of the same character to explore how easily we replicate harmful patterns of exploitation, even when venturing into the stars.

The story follows Mickey Barnes, an “expendable” worker in a space colonization mission to the ice planet Niflheim in 2054. Mickey signed up for this job without reading the fine print, a decision that led to his dying and being “reprinted” with his memories intact seventeen times. This premise serves as the perfect vehicle for examining the ethics of human expansion and colonization.

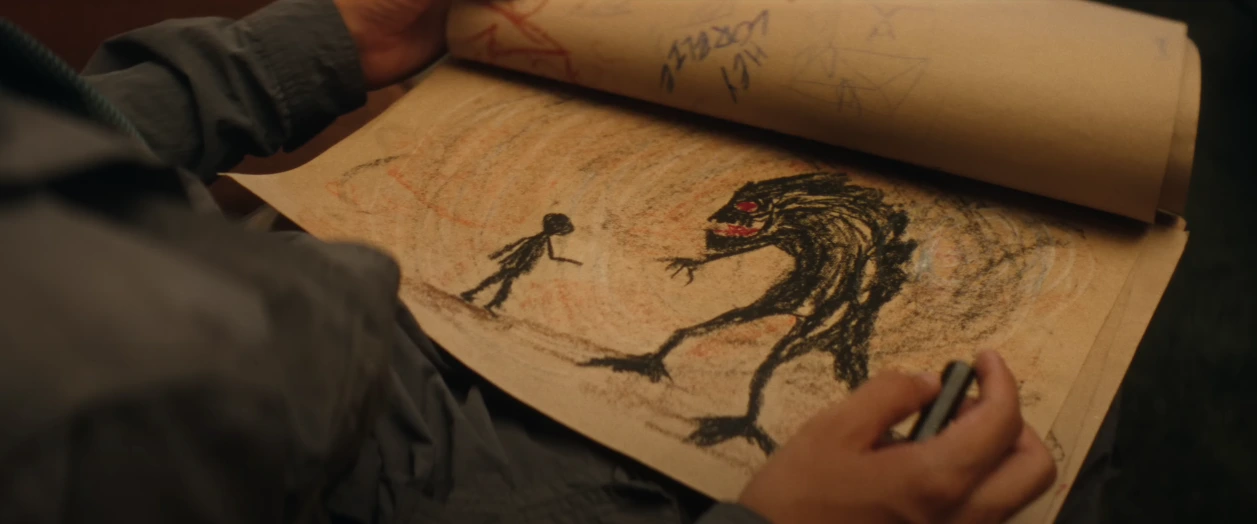

When humans arrive on Niflheim, they immediately treat the native inhabitants, called “Creepers,” as threats rather than sentient beings with their own rights. The expedition leader, failed politician Kenneth Marshall (played by Mark Ruffalo), sees the ice planet as his chance to create a “pure” society of loyal followers, with no regard for indigenous life

The film pointedly mirrors historical patterns of Earth colonization, where newcomers arrived with assumptions of superiority and claims of bringing “civilization” to new lands. Mickey’s role as an expendable worker also reflects how colonial powers viewed certain groups of people as disposable in service of expansion.

Mickey’s personal journey becomes central to the film’s exploration of colonialism. At first, he accepts his expendability, feeling he deserves punishment for past mistakes. His seventeen deaths and resurrections represent the cycle of exploitation that often characterizes colonial endeavors.

The introduction of Mickey 18, creating two versions of the same person, adds another layer to the film’s examination of identity and consent. The two Mickeys must hide their dual existence from authorities who would eliminate them both, forcing them to question what makes them human beyond their usefulness to the colony.

This duality creates tension around the idea of consent in colonization. Neither Mickey truly consented to his role as an expendable, just as indigenous populations never consent to being colonized. The system works by treating certain beings as less worthy of consideration.

Bong Joon Ho cleverly uses the relationship between humans and Creepers to question our assumptions about first contact and territorial rights. The natives of Niflheim initially help Mickey rather than harm him, challenging the colonizers’ presumptions about their hostility.

The film’s portrayal of Marshall and his wife Ylfa (Toni Collette) takes direct aim at the intertwining of capitalism, politics, and colonialism. Marshall’s cult-like following and authoritarian leadership style show how colonizing missions often serve the ego and power of their leaders rather than any noble purpose.

Marshall’s character serves as a caricature of political figures who use religion and nationalism to justify expansion and conquest. His vision for a “pure” colony on Niflheim reveals the uglier motives that often lie beneath colonial rhetoric about progress and civilization.

The ethics of the “expendable” program itself raise profound questions about how societies assign value to human life. Mickey’s repeated deaths for the colony’s benefit represent the expendability of workers in exploitative systems, whether in colonial outposts or modern corporations.

What makes Mickey 17 particularly compelling is how it connects historical patterns of colonialism to potential future space exploration. The film suggests that without confronting our past, humans will simply transport the same problems to new frontiers.

The film’s conclusion offers a glimpse of hope when Mickey destroys the cloning device, ending the expendable program. This act represents a rejection of systems that treat lives as disposable and suggests the possibility of building relationships based on mutual respect rather than exploitation.

This moment of rebellion against the colonial system shows that breaking cycles of exploitation requires active resistance. Mickey’s choice reflects the film’s central argument that consent and respect must be at the heart of any ethical human expansion.

The tentative peace established with the Creepers by the end of the film suggests an alternative model of coexistence. Rather than conquering or displacing the native inhabitants, the humans begin to recognize them as equals with their own right to the planet.

The film ultimately leaves viewers questioning what true ethical expansion might look like. Can humans move beyond our history of colonialism to form genuine partnerships with other beings, or are we doomed to repeat our worst impulses wherever we go?